David Hockney: 20 Flowers and Some Bigger Pictures

I didn’t know what to expect with this Hockney show at Pace, only that I knew he had been working in France, using an iPad instead of paints and canvas. The modesty of the title of the show, “20 Flowers and Some Bigger Pictures”, also downplayed expectations. iPad paintings of flowers from France, should be pleasant.

It would be easy and understandable for Hockney to dial it in at this point in his gargantuan life. Escaping to the French countryside — we were all looking to get away during the pandemic — might juice the pathway to some new work, dispatches from the pastoral. But Hockney’s game has always been bigger. His curiosity has long revolved around a materialist conception of art history, especially regarding the impact of technology on visual perception. His study of Renaissance painting led to a controversial thesis on the role of optical instruments, like special lenses and special cameras, in the creation of works by Van Eyck and others. He has constructed “Cubist” Polaroid collages which play with multiple, simultaneous perspectives. I also remember being surprised while watching an art history video, by his perceptive remarks on visual perspective within ancient Chinese scroll paintings.

This show displays his current lines of investigation into art and technology, and they are thought-provoking. In an appealingly modest voice, Hockney introduces his new show in some wall text: how the titular flowers came to be, the use of multiple iPads in the making of some of the works, and his ongoing experiments with a new line of picture-making, which he calls photographic drawings. He also has some remarks about the inkjet printing process.

About half the works are the multiple iPad works, large scale pictures with grid formats, the number of grid cells matching the number of iPads used in their creation. While they do investigate the fracturing and simultaneity of perspective that he has pursued in his older photographic collages and paintings, they also absorb us in the play of extended perception with the natural world. The length of time to create iPad paintings en plein air is probably less than for traditional painting, but more than for a photographic collage. You can sense the tempo of incipient raindrops, and the slight shifting of shadows. The technology brings to the fore other highlights. The inkjet colors pop, and the large scale allows us to see color transitions and the variety of edge treatments. The unfussy virtuosity on display is engaging and welcoming.

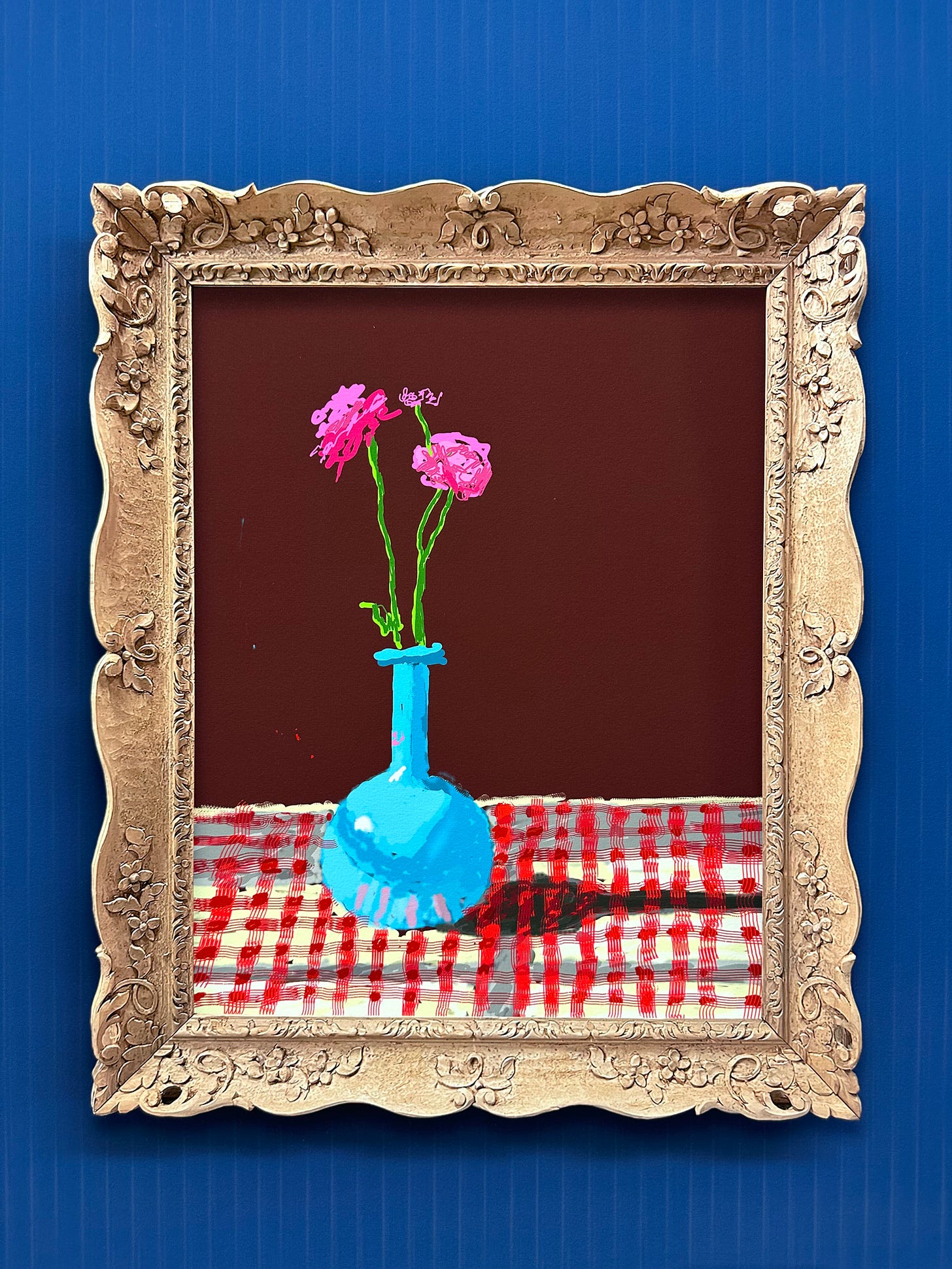

More thought-provoking were the remaining works, whose subject was the 20 flowers, but presented in several ways. The largest presentation shows the 20 flowers, each with an ornate wooden frame, mounted on a blue wall, with 2 seated Hockneys and furniture in the foreground. It’s pictured below: more than 20 feet wide, and composed of 5 vertical panels, each presumably the width of an inkjet printer. You can smell the slight static charge of the inkjet printing. The presence of 2 Hockneys clues us into his interest in time and simultaneity. The much stronger impression is of the incredibly 3-dimensional presence of each object in the work. The detail shots below show how incredibly ‘present’ the objects seem. In his wall text, Hockney describes a little about the new process he is using to create this image. He calls this process photographic drawing, and it involves taking a 3D photograph of each object, which I interpret as a kind of 3D scanning of an object. I imagine these scans then exist as 3D models on a computer, and subsequently can be composited to produce the larger work. In the final work, each object achieves a hyper-clarity, which seems almost unreal. It likely feels almost unreal because it departs from our normal human vision, or it is an augmented version of human vision, as the 3D photograph contains multiple, continuously differentiated viewpoints in its process. The shadows cast on the floor by the furniture, and the shadows cast by the wooden frames on the blue wall, have a diffuse, vestigial quality. There is a uniformity in the light reflected by these objects, offering a small glow to each.

Curiously, there is a smaller version of this mammoth work in the show. The smaller version is I’d guess about 8 feet wide, and it’s on a wall near the bigger version. It wasn’t clear why there were 2 versions of the same work somewhat adjacent to each other. The smaller version didn’t have the same remarkable effects of the larger. I wondered if there was a pedagogical direction to their display, that the difference in scale leads to differences in the perceptual effects of Hockney’s technological process. It could be an invitation to the viewer to accompany him on his journey.