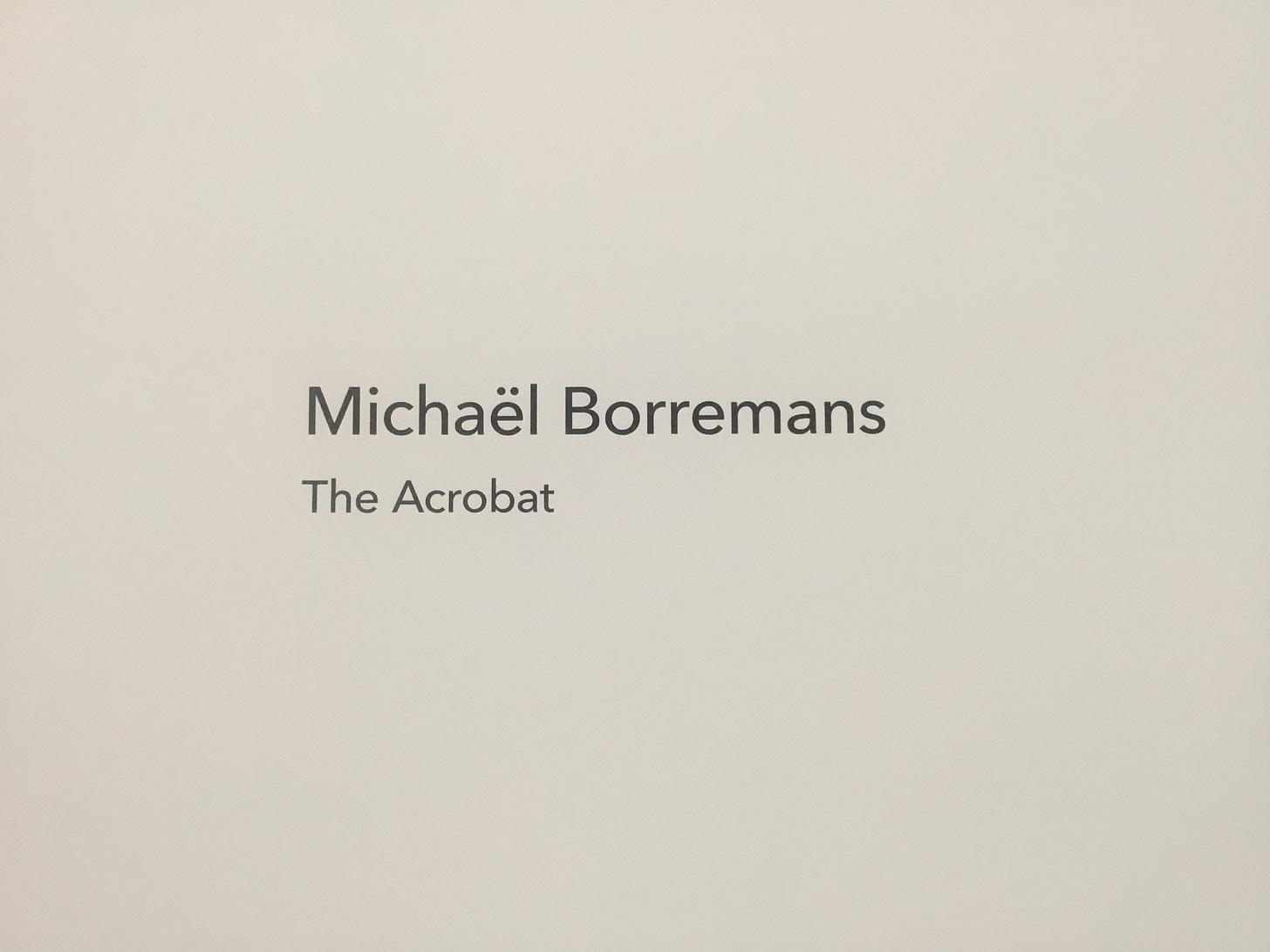

Michaël Borremans: The Acrobat

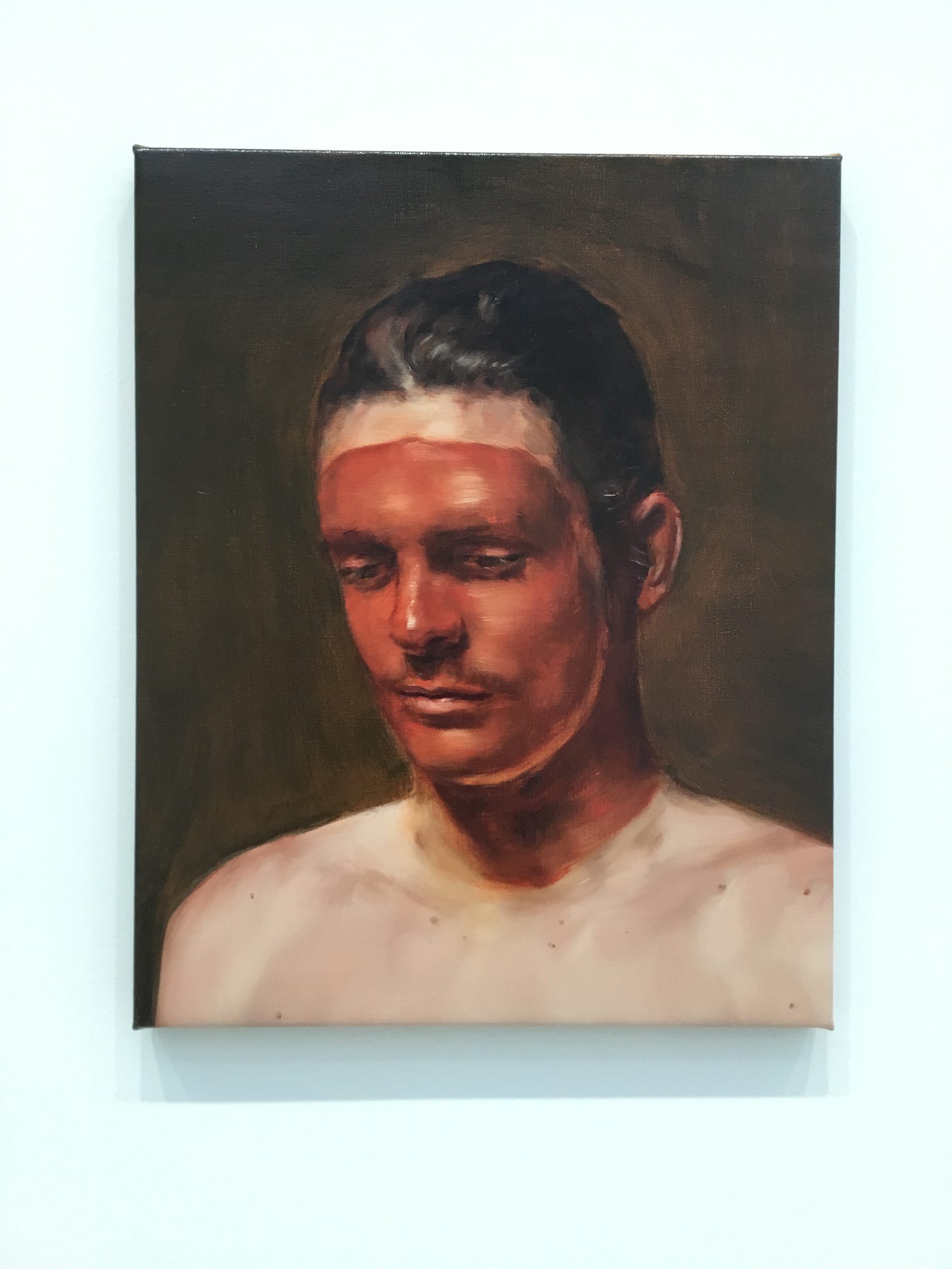

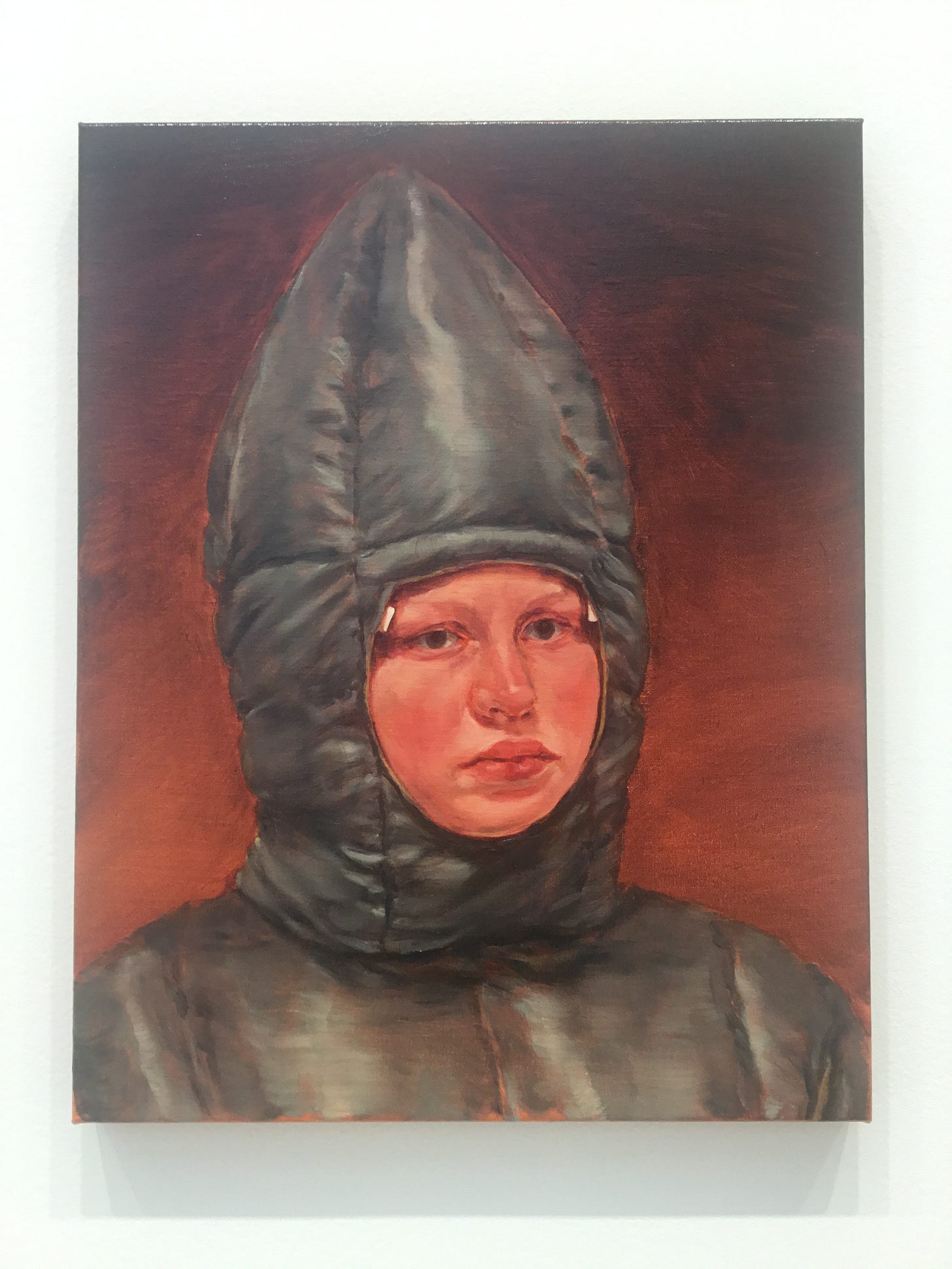

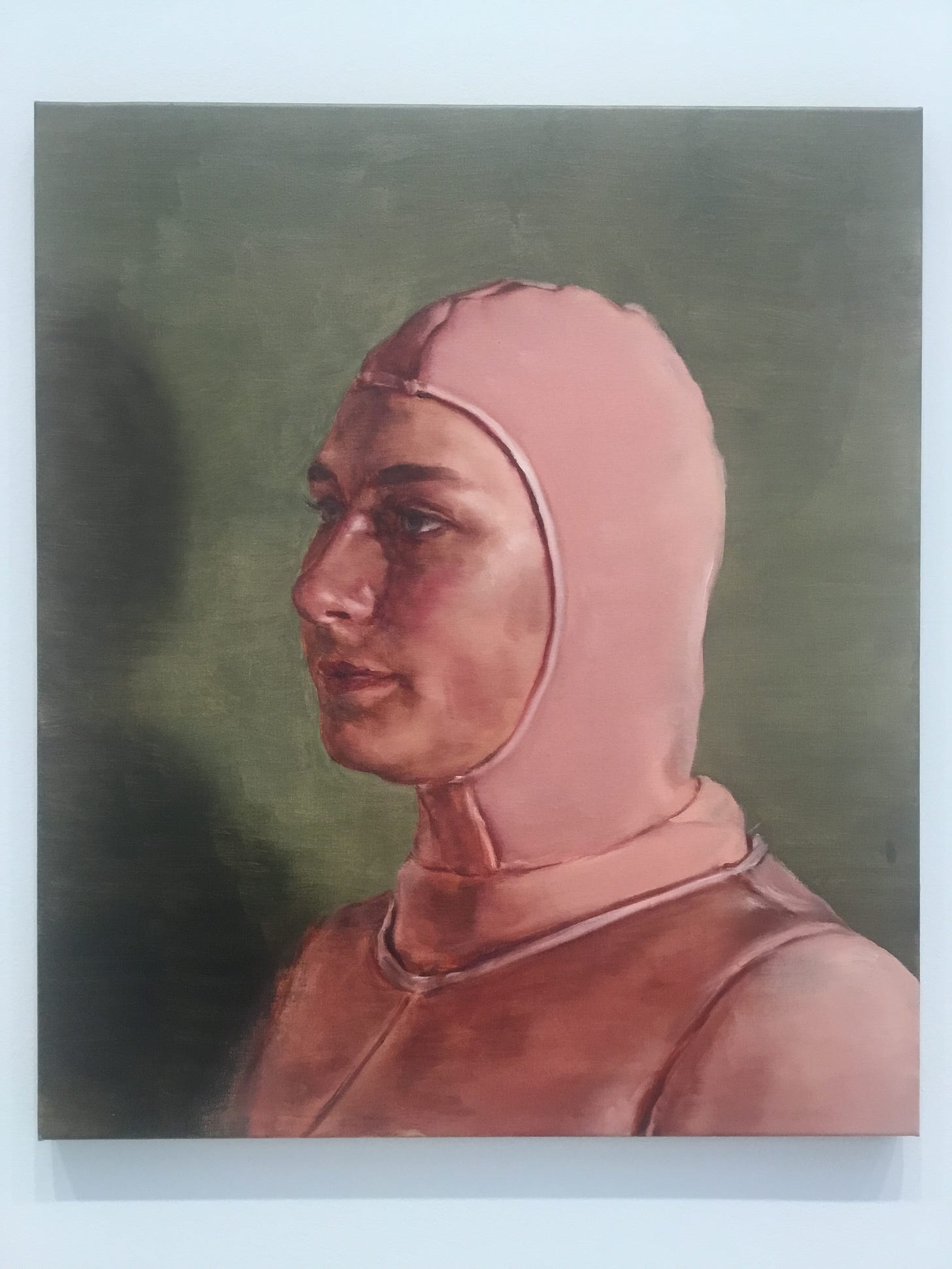

The paintings, all similar in format, of ‘characters’, centered within their frames, portrayed from waist up or more closely on the head, hang in one room. None look at the viewer. (Borremans says he does not paint portraits.) They have distinctive carnival-esque garb or body makeup. The painting titles (The Racer, The Acrobat, The Witch, The Cutter) could denote roles in a theater production. The subjects sit still, registering little emotion, blank or pensive or diffident, not ‘in character’ for whatever theater production they may be a part of. The setting is before or after the production, so they are getting dressed and ready, or they are finished for the time being.

Being before or after the event is the mood of these paintings in the main room of the gallery. In the darker, smaller room, the mood is similar. I wasn’t able to get good pics of these small works, since they were inside a vitrine, and there was glare in the photos. These works are paintings on cardboard or similar, one has markings of packaging, like a saved piece of an empty wine box, and the painting treatment is looser, draft-like. Each small painting depicts a glass vitrine containing human figures, being viewed by figures outside the vitrine, and the perspective is from a vantage above, not directly overhead, but you can see the figures in the vitrine, along with the viewers looking at the vitrine. The dress of the figures within the vitrines is from the past, suit-like, back when people wore suits when they worked. There is an Old World feel to the figures inside the vitrines, but the world outside the vitrine does not look especially new. The world outside the vitrines looks almost contemporaneous to the world inside the vitrines. There is one hint of a modern elevator lift to deliver viewers to the level of the vitrine, but the lift platform is only sketched out with little attention. The mood is clearly retrospective, and the titles, like Five Writers (Design for a Sculpture), put us in mind of museological preservation and display, but of specimens of human roles or typologies.

Both rooms of paintings bring to my mind the facies hippocratica, the face of death, Walter Benjamin’s wonderful image when describing the allegorical way of seeing, of viewing “history as a petrified, primordial landscape.” The paintings give off some of the same mournfulness evoked by Benjamin:

Everything about history that, from the very beginning, has been untimely, sorrowful, unsuccessful, is expressed in a face — or rather in a death’s head.

The figures in Borremans’s paintings from the main room are all youthful, but their mood, as well as the painting titles (eg The Witch), encourage an allegorical way of seeing, one that sees the death’s head of history imprinted in the world around us.

I could be thinking of Benjamin here also because his exegesis of modern allegory comes from his study of the Trauerspiel, or lamentation play. Benjamin describes the Trauerspiel as “a caricature of classical tragedy”, or “an incompetent renaissance of tragedy”, or “plays written by brutes for brutes”. (I can’t resist dropping Benjamin’s delicious quotes!) They are meant to be seen as theatrical productions, rather than read, as we might for Shakespeare. They pile on visual emblems, and dramatic mannerisms, which, for Benjamin, epitomize the allegorist’s handiwork. I see Borremans’s mode in these works as primarily allegorical. Borremans’s figure paintings seem to take place in a theatrical setting, but off-stage. This setting, and their costumes, and the painting titles, encourage us to read them as theatrical personas. Due to their subdued demeanors, I sense an air of the tragic, or the comic as tragic, in his figures.

As I left the show, I bought a copy of the book which accompanied the exhibition. The texts in the book were written by Katya Tylevich. It was my first encounter with her writing. Check out these quotes by Tylevich:

Perhaps the many texts asserting that Borremans “creates his own worlds” miss the joke. He re-creates our world in his own way. Like literature’s most memorable passages, Borremans’s art communicates what we know already but could not say ourselves.

and

While Borremans’s paintings do not directly quote other artists, they make like-minded wisecracks. The found object on display is the humor, stretched across ages. One need not be an art historian to get in on the joy of it; simply being alive should do it.

That’s an amazing voice.